Figure it out, in three years of karate, I have learnt only one kata! During class, my sensei made me ‘repeat the same kata hundreds of time, for hours, days, months, until he considered I had assimilated it and understood it.’ With time, I understood that ‘only a great will, a great motivation and a total loss of ego can allow the mastery of a martial art.’ Those word are not mine, of course, but do you know who they belong to? I invite you to discover it through this reflection on kata.

For the non-practitioner, a kata is often like some kind of a choreography, even if karate techniques can be perceived through it. For a beginner in karate, it is more like a series of codified moves you have to memorize in order to get a new belt (kyu). However, for the advanced karateka, what a kata is will be more obvious and clear…

Ask them and they will most certainly will answer what their teacher told (and were told by their own sensei, etc.), that is to say, a kata is :

- an imaginary combat against several imaginary opponents,

- an imaginary combat against several real opponents,

- a real combat against one or several imaginary opponents,

- a real combat against one of several real opponents…

Up to this point, if you feel like being tricked or start doubting, it is a pretty good sign (I was there too in my first years of practice)! To progress in karate, you should, I think, try to understand, to open you mind. Is it a good thing just to mimic/repeat what you were taught, without reflecting on it or trying to challenge it? Problem is, even for long-time teachers, what they were taught might have been wrong or misunderstood. A simple analysis will help us understand that those definitions of what a kata is are not realistic.

Oh yes, I almost forgot: “kata” in Japanese translates into ‘form’ or ‘mold’. This you already knew, but it is not the most important thing to remember.

A kind of individual training?

The fact that kata is practiced ‘alone’ can lead to a misunderstanding, making us think that we are only facing ‘imaginary opponents’ and that we must ‘visualize’ them when doing each technique. Why not? And after all, that is an interesting kind of an exercise (are you doing it in your dojo?), but:

- did you know there are katas in judo and aikido too and that you don’t practice them alone but with a partner (fundamental codified sequences/forms)?

- while training in karate (Shotokan, Shito-Ryu, Wado-Ryu, etc.), did you ever practice Ten-no-kata, alone in its omote form and with a partner in ura?

If your answer to both questions is no, maybe you are not interested in traditional karate and in the history of martial arts: you have to right to do so, I had been in this case myself for years (at least before I started to be a teacher). Of course, one may focus on physical conditioning and aesthetics through kata practice. That is what athletes in sport karate do. However, never working on techniques with a partner is missing the very essence of the kata.

One or several opponents?

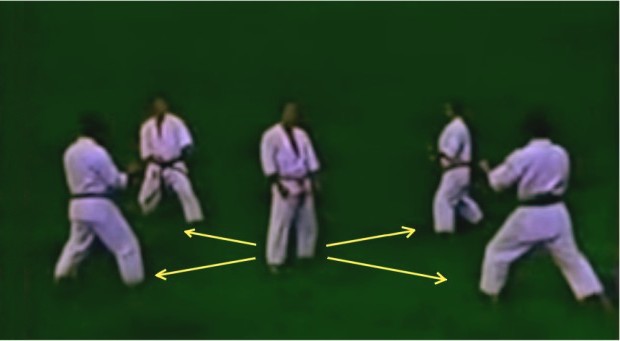

Most katas include moves and movements in various directions, in addition to frequent U-turns. This may suggest that we are facing several opponents during this ‘fight’. Why not? Indeed, it is important to train against multiple opponents (are doing that in your dojo?), however:

- do you think you are able to defend yourself against a determined, smart and maybe armed aggressor who planned his attack and manage to take you by surprise?

- despite years of practice and mental preparation, are you sure you will not be disturbed or even paralyzed by fear, stress and danger, when it comes to defend yourself?

Of course, I hope you will never have to face such a situation. Unfortunately, as it is already difficult and dangerous to defend against one aggressor, it seems unrealistic to believe that a kata aims at teaching us to fight 4, 5, even 10 opponents. So, the kata would then be a combat against one opponent? A drill to work with a real partner? That is better, but we are not exactly there yet.

Is the kata a representation of a fight?

A kata is made of dozens of movements and techniques. Its execution generally lasts between 1 and 2 minutes. We may think that each kata describes a codified combat, from beginning to end, against one opponent. Why not? Moreover, practicing the full sequence of techniques with a partner is indeed a great exercise (are you doing that in your dojo?). However:

- how many defensive actions/parades have you done during this fight (congrats by the way!) and how many deadly blows have hit your opponent (not that effective, obviously)?

- have you ever witnessed violent fight situations (in the streets, without rules or protective gear)? If so, have you seen the opponents hitting each other for long periods of time?

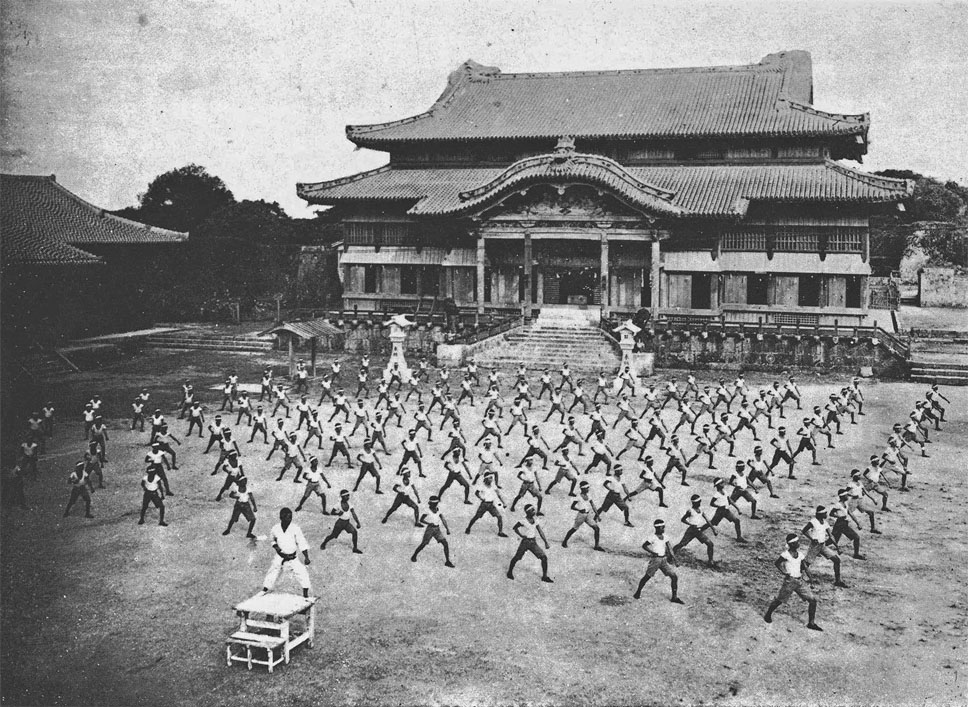

In a real combat situation, everything goes very fast and is generally a matter of seconds, at most. So, it is not realistic to think that a kata will teach us to combine dozens of techniques (even more in an established pattern). A kata is more about learning short sequences, applicable in self-defense. Actually, we know that the Okinawan masters who taught karate (long before its opening to a wider audience in the beginning of the 20th century) granted much importance to kata training: the main goal of their martial art training was to defend themselves and their family from life-threatening situations.

The kata: a defense system

The katas are the legacy of the grand masters (they even sometimes bear their names). In a way, they are a codified synthesis of their self-defense knowledge. In addition, teaching a kata favors the transmission of this knowledge from a generation to another.

There are many katas (more or less depending on which karate style), some of them including a wide range of variations. Some are very specific of a given style, others share the same origin but were altered over centuries of practice and from a ryu to another. You did not know? Modifications in katas have always existed, long before sport karate.

Indeed, if we consider that a kata (its ancient form) represents a defense system, it is easy to understand why, over time, techniques were added, deleted, modified: effectiveness, or not, tested on the field of combat, adaptation to practitioners’ morphologies, secret oral transmission to one or two followers only, wrong interpretations and even willing alterations…

This is why, if you consider a kata being a defense system on its own, you cannot just practice it, or just list the techniques: you need to go further in its study and consider the kata as complete a self-defense training method.

How to study a kata?

To study a kata in depth and be able to use it for self-defense purpose (once mastered), here are some ideas I want to share with you:

- study of the correct form of each isolated technique (everything that is in the kata is important)

- practice of the kata: diagram (embusen), coordination, slow/fast movements, balance, timing, muscle memory, strength training, etc.

- implementation principles: positioning, breathing, stance, speed, relaxation, contraction, use of the hips, kime, etc.

- tactics & global strategy: types of parade & attacks, feinting techniques, counters, defense zones, vital spots, etc.

- sequences analysis (bunkai): this point, specifically, is a substantial work of research

- bunkai applications in sequences of a maximum of two or three techniques (e.g. Block, counter, lock)

- bunkai applications in free fight (ideally against realistic attacks, with or without weapons): adaptation, timing, realism, etc.

- resistance, effectiveness, precision, determination and mental training (e.g. full strength makiwara training)

- application of teachers’ oral explanations, all that is not necessarily ‘visible’ in the kata

- study of the kata’s variations and its forms in other karate schools/styles (don’t believe that your style is the best)

- repeat and work again and again on all those aspects: for instance, some karate masters consider you need to practice a kata from 3 000 to 5 000 times to start ‘feeling’ it!

This list is not meant to be comprehensive, so imagine the sum of work it represents: how many years of practice would be necessary to start mastering all those aspects in a kata (even though we would have access to the teachings and explanations of its creator)?

Why only one kata in three years?

Now you understand why most karate masters had extensive knowledge on few katas only that they would teach (in general one or two katas). Of course, they were studying other katas, but not as deeply, so they would not feel like transmitting correctly the essence of those…

In his book Karate-do: My way of life, Gichin Funakoshi recalls that he started to train in karate at 11 under Master Azato. The latter had him train exclusively on the first tekki (naihanchi) kata, for three years: back them, Funakoshi found that tiresome, exasperating, even humiliating sometimes. However, he made a motto out of “hito kata san nen” (one kata in three years): it was a common saying among karate masters at the time. Actually, this saying does not mean that you need three years to learn a kata, but rather that it is the minimum of time required to have your body assimilating the moves.

Of course, today, it is hard to imagine that you would teach only one kata during three years (to adults or kids alike). Indeed, karate practitioners always want to learn more and to learn fast. Nevertheless, we all agree on the fact that quantity is at the expense of quality. Because of this, I encourage you to choose one kata that will be your favorite (tokui kata): study it in depth, for years, to make it yours and to get the maximum out of it. Who knows? Maybe this will give you the keys to understand the other katas…

Are you ready to dive deep into karate thanks to katas?

Author of the article

Karate Instructor

6th Dan - BEES 2